RIGHT FORK DESCENT, 1965

Our trip began 7/17/65. At this time, the owners of the Sunset Canyon Ranch did not want persons crossing their land. The easiest place to enter the canyon we felt, was from the lava flow on the North Creek drainage. We left the road at the Park boundary, crossed the flow, and descended to the creek. There are numerous places to descend safely.

Close inspection of the map will show a trail on the north side of the creek which goes as far as the Left Fork. Even closer inspection is required to actually find the trail, but once found will save a little stream-hopping. At Trail Canyon (Tributary #1), the creekbed widens into a small flood plain. Near here is an old circular corral. From here to Tributary #7 (approximately 4,500) simple rockhopping is required. Shortly beyond here a pool about three feet deep, extending from wall to wall, presents itself. Here one can backtrack a little ways, climb out of the inner creekbed (approximately twenty feet deep), and beat his way along some deer trails through the brush and emerge on the other side of this pool. Or, of course, he can wade through. It isn't very long (10 feet or so). As one goes up the canyon, the stream appears clearer and diminishes in size. The tributaries contribute to the size of the stream. As I recall both tributaries 5 and 7 were running.

If a line is drawn from Peak 6,818 on the north to Peak 6,470 on the south, the line will intersect the stream where a waterfall is located. (Editor's note: current maps show slightly different elevations.) Here I must get a little subjective. The fall, in form, is one of the most beautiful I have seen. It flows over a hard layer of sandstone that is about one or two feet thick. Under this layer is about 10 or 15 feet of less resistant rock. Consequently, the back of the falls has been eroded away to a depth of about 10-12 feet resulting in a free leaping, falling stream of water. There is profuse vegetation from here until the water in the stream stops flowing further upstream. Hanging gardens abound!!

The boulders in the stream continue to increase in size.

This first waterfall can be easily passed by going up the hill on the south side starting up about 30 feet from the falls. One has to depend on a bush now and then but the falls is easily passed.

About 1/4 mile upstream, another falls is encountered. It is another straight falls but is not concave behind. There is much vegetation growing in the falls itself. The falls itself is a montage of water and vegetation. It is passed by an easy climb of about 20 feet around the north side of the falls.

Another 1/4 mile or so of boulder hopping brings one to another falls. This one is at the beginning of the narrows where the sheer walls of the canyon converge. This one is the most difficult to this point, in my opinion. We used three different routes on this one.

One route is to the north of the falls. A climb up a foot wide crack leads to a large tree growing in the crack. At this point, about 75 feet above the creekbed, a ledge (of sorts) traverses horizontally to a point above the falls. The ledge slants downward. It was not a comfortable traverse for me. I wouldn't want to do it with a pack.

The other route is on the south side of the falls. It is a rock scramble for about 50 feet and a somewhat vertical climb for about 20 feet with a dropoff awaiting anyone who loses his hold.

After someone has successfully passed one of these routes, a third one is possible. A rope can be lowered directly down the face of the falls and ascent can be made by holding the rope and walking up the face of the falls.

This falls is somewhat dome-shaped with a chute pouring out on the quarter-dome. Moss and other vegetation is quite profuse. The rock is bright red with dark but brilliant streaks of moss running through it. Here the bottom of the Navajo Sandstone is and there are seeps everywhere. This whole corner is green with this brilliant red shining in the middle. Below the falls is a large pool.

We named this Knapsack Falls. At this point, after we had successfully climbed the falls, we were pulling our pack up by a rope when, as the pack was nearing the top, the knot gave way and down 75 feet into the waterflow our pack. All our equipment was broken. After one negotiates one bend in the stream, the Stevenson Alcove comes into view. For the sake of nomenclature and also in respect for the man is the reason for this name. Adlai E. Stevenson passed away only a few days before we entered this area.

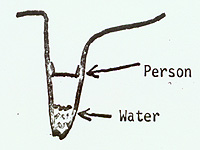

This alcove is a large semi-circular, dome-shaped room cut into the Navajo by the stream, (which incidentally still runs here). The roof is approximately 100 to 150 feet high. Here is where the true narrows begins. The stream has cut a narrow slot in the rock and in many places, for the next quarter mile or so is over six feet deep and must be passed by feet on one wall and hands on the other.

With two people along on the trip, it would be advisable, I believe, for one to go through without any clothes on. When the streambed begins to level out a very easy traverse will bring the hiker back above the alcove floor approximately fifty feet up on a ledge. Here the clothes, pack, etc., can be raised by rope without danger of a dunking. Then, of course, the other may then follow.

With a little rock-climbing skill and possibly a little equipment, a climb could be made directly to the ledge thus avoiding the water altogether.

Once past this alcove the going is very easy. Fifty foot boulders occasionally block the way but none are difficult to get around. The water ends about 300 yards above the alcove. No more seeps from here on.

A line drawn from Mt. Ivins to Peak 6,991 on the north will cross the stream at the location of the next obstacle. There is a narrows full of water. It can be overcome fairly easily by a short climb around it to the right of it looking upstream. It looks easier to the left but...

Incidentally, the tributary to the north in the narrows (tributary #9) drops about 50 sheet feet to the main streambed. There is one crack a skilled climber may take advantage of, but not I.

The last obstacle we ran into (our Waterloo) was approximately 1/8th mile from the West Rim (where the stream forks to the North and South). The canyon has an extremely low and narrow channel at this point. It is lower than the normal gradient here consequently is full of water. The water is surely over six feet deep and probably at least 150 feet long. The channel is about three to six feet wide and 25 or so feet above the level of the water. There is a shelf on each side after the channel widens. The water is NOT good for drinking; it is very cold. The shelf on the north might be traversed beyond the water, then one could lower by rope about 25 feet to the streambed. Much skill at friction climbing or some equipment will be needed here. We couldn't see beyond the bend.

I climbed up the little canyon to the north hoping to emerge on the west wall of the canyon beyond the fork opposite the West Rim. I found a large berry bush 500 yards or so up the canyon and ate some and didn't get sick. So at least a little food is available here.

The canyon got too steep for me but at this point, I was tired and out of food and had to return. From the West Rim Trail, it appears that one would be in good shape if he could get out of this canyon onto the slickrock bordering the west side of the Great West Canyon.

To me and Bill also, the trip would be worth it (and was) just to see the Alcove and waterfalls, I believe the canyon could be hiked to where we turned back in one long day. We made it to Stevenson Alcove in our first day.